A sacrificial attack that you are unable to take to a successful end (the realization of your aims) becomes a liability. If the opponent can defend successfully and thwart your attack, you are faced with the handicap of not only a deficiency in material but also loss of time and to regroup your pieces may become impossible. Your opponent will exploit your weaknesses to create his own attacks which you will possibly be unable to resist. The outcome is the opposite of what you intended with your sacrifice.

A badly planned or calculated attack is a wrong chess tactics that is always doomed to failure. But a frequent cause of your inability to conclude the attack is the inadequacy of your force at a certain stage to sustain the attacking tempo. So an accumulation of adequate forces is a part of your chess tactics prior to the launch of a sacrificial attack as you were told in Chess Sacrifice as Chess Tactics.

But an adequate accumulation per se is not enough. You must be able to make your sacrifice at the soonest possible opportunity to get the success. In chess, every move counts and if you delay or hesitate, the opponent may be able to guess your intention and a major reason for success of sacrifice, the surprise element, will be lost. Moreover, the delay will enable him to bring in more defenders that may totally refute your attack.

So the elements of a successful chess sacrifice are:

- plan out the combination with your opponent’s possible reactions in mind

- accumulate your forces and position them through tactical maneuvers

- this process itself may involve some secondary sacrifices and that is why you often find that sacrificial attacks involve a series of sacrifices

- while doing so, maintain the surprise element (some sacrifices in the previous step may be diversionary tactics!) by trying to hide your intention, keeping for last the move that may be a giveaway

- while making these preparations, just don’t be so blinded by your own clever plans that you fail to notice what your opponent is doing and its impact on your plans

- as soon as you think that your preparation is ready, initiate your attack with sacrifice

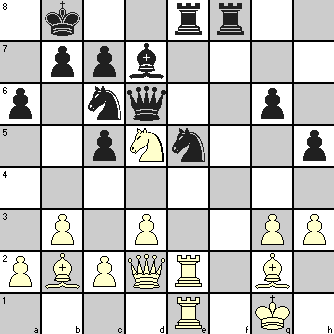

Here we present a game between Herman Pilnik and Miguel Najdorf that was played in a 1942 tournament held at Mar del Plata in Argentina.

Herman Pilnik (1914-1981) was born in Germany but emigrated to Argentina and became an Argentine Champion. He was awarded IM title in 1950 and GM in 1952. He later moved to Venezuela and stayed there till his death.

Miguel Najdorf (1910-1997) was a Polish master of Jewish origin. When he was in Argentina to play a tournament and WWII broke out, he decided not to return home and took Argentine citizenship. That saved him but not his family who perished in Nazi concentration camps. He became a Grandmaster in 1950. He was a profound theorist and contributed to many openings, the most famous being the Najdorf variation to Sicilian Defense which is used widely in master games.

The game illustrates our points on chess sacrifices regarding how the initial preparations are made and a series of sacrifices are planned to deliver the final blow, after which the last few moves towards a win become a formality! The attack is so brilliantly executed that you will feel as if all the moves by White constitute a long tactical combination!

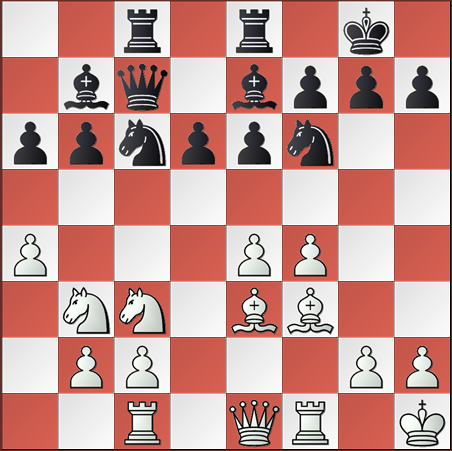

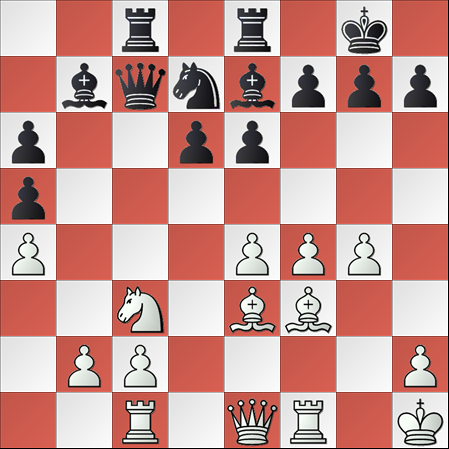

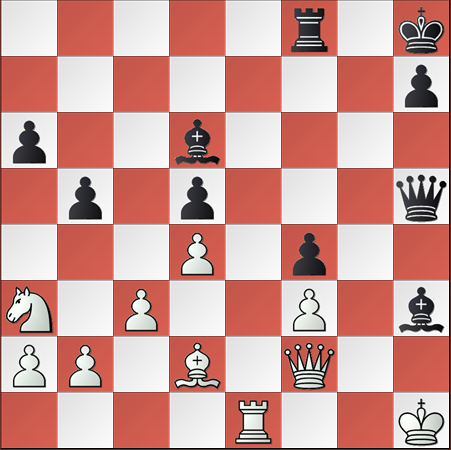

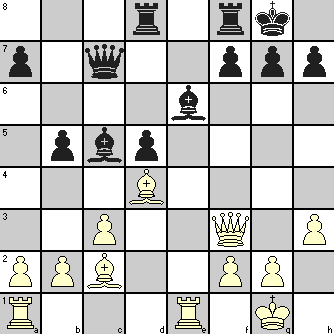

The diagram position occurs after 13 moves, though it is worth going through the whole game for the reasons mentioned in the previous paragraph as White started his manipulations as early as the 8th move!

The game went as below

(Note: The analytical comments are from one of the books of Fred Reinfeld where this game was a part of the collections.)

| 14. | cxd4 | Re8 | Black’s move looks normal, but as can be seen later, 13. … Be6 would save a lot of trouble! |

|

| 15. | Bc4 | h5 | White threatens 16. Bxf7 Kxf7 17. Qxh7+ Black’s pawn move only helps to weaken the castle |

|

| 16. | Rae1 | Re4 | ||

| 17. | Nf4 | Qxd4 | Look how White is maneuvering his pieces in position and keeps creating new threats like 18. Rxe4 fxe4 19. Nxg6 and then 20. Qxh5 to demolish the castle completely. |

|

| 18. | Rxe4 | fxe4 | If 18. … Qxe4 then 19. Nxg4 Qxh4 20. Nxh4 wins for White because of Black’s poor K-side pawn structure. |

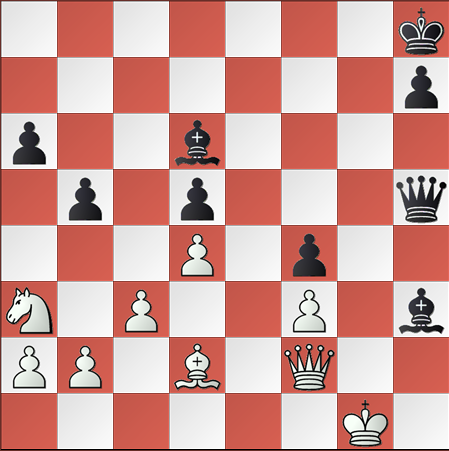

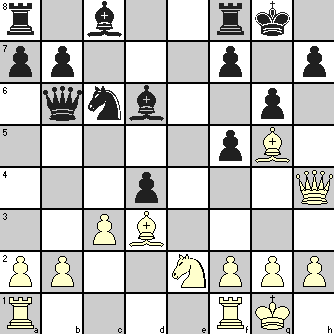

At the end of the 18th moves, the position stands as shown.

| 19. | Nxh5 | gxh5 | If 19. … Qxc4 then 20. Nf6 with mate to follow soon. |

|

| 20. | Bf6 | Qc5 | 20. … Qxc4 results in 21. Qxh5 followed by 22. Qh8# |

|

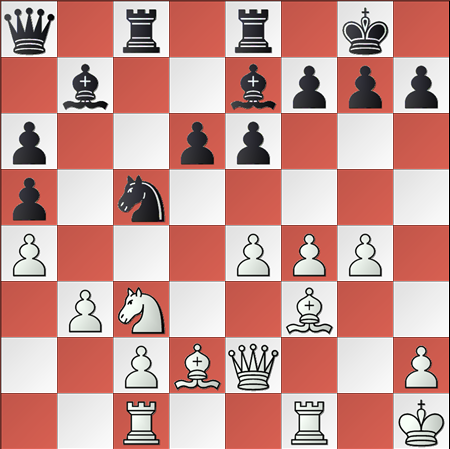

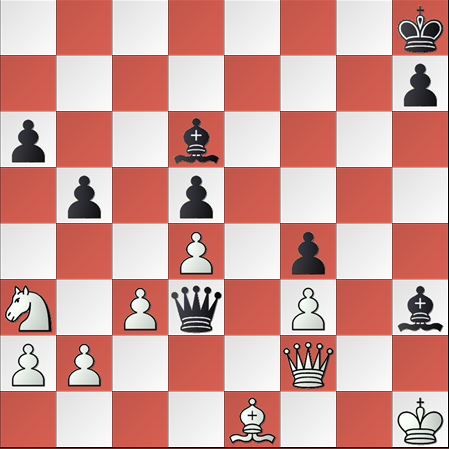

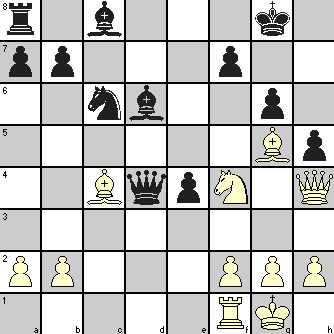

| 21. | Rd1 | The threat of 22. Rd5 creates many possibilities, all bad for Black! 21. … Be7 22. Rd5 Bxf6 23. Qg3+ wins Black Q 21. … Be6 22. Rd5 Qxc4 (21. … Bxd5 22. Qxh5 leads to mate) 23. Qg5+ Kf8 24. Rxd6 wins 21. … Bg4 22. Rd5 Qxc4 23. Qg5+ Kf8 24. Rxd6 wins 21. … Ne7 22. Rxd6 wins for White |

||

| 21. | … | Kf8 | ||

| 22. | b4 | Nxb4 | If 22. … Qxc4 then 23. Qxh5 (not 23. Rxd6 as Black wins with 23. …Qc1+) Ke8 24. Rxd6 as 24. …Qc1+ is now met with 25. Rd1 So the Pawn sacrifice diverts the Knight to create the possibility of combination comprising White’s 23rd and 24th move |

|

| 23. | Qg3 | Bg4 | 23. … Bxg3 24. Rd8# (would not be possible with Black Knight at c6) |

|

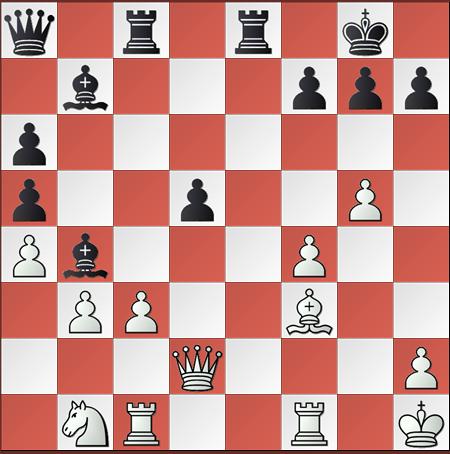

| 24. | Rxd6 | Nd3 | 24. … Qxc4 25. Qf4 and Black has no good response to mate threats after 26. Qh6 | |

| 25. | Bxd3 | Qc1+ | ||

| 26. | Bf1 | Rc8 | Black threatens 27. … Qxf1+ 28. Kxf1 29. Rc1+ leading to mate | |

| 27. | h3 | Qxf1+ | ||

| 28. | Kh2 | Qc1 | 28. … Rc1 29. Rd8# | |

| 29. | hxg4 | hxg4 | ||

| 30. | Qxg4 | Qh6+ | ||

| 31. | Kg3 | Rc3+ | ||

| 32. | f3 | Resigns | There is no more hope left now! With Pilnik’s series of sacrifice offers, Najdorf might have had in his mind a precursor to his famous comment* about Tal made nearly 30 years later! |

*”When Spassky offers you a piece, you might as well resign then and there. But when Tal offers you a piece, you would do well to keep playing, because then he might offer you another, and then another, and then … who knows?”