Many may continue on the same path for a distance, but you never know where they will end ultimately! We are talking of chess games.

This divergence becomes more prominent when one game is controlled by a player who follows the dictates of chess strategy (should we say sanity?) and the other by one who could not care less, a maverick who cannot let go of any opportunity to shock his opponent (and the world at large)!

Before we open the ‘show’, here is a brief introduction to the ‘actors’ in the ‘plays’.

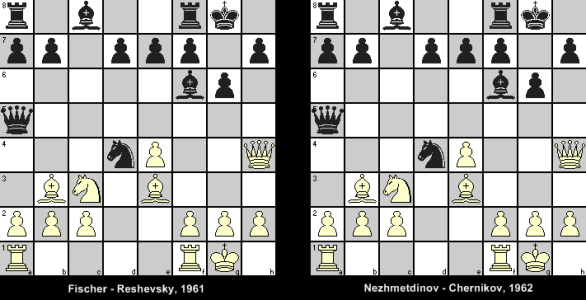

The first game was played in 1961 between Bobby Fischer and Sam Reshevsky, the second one in 1962 between Rashid Nezhmetdinov and Oleg Chernikov.

Bobby Fischer (1943-2008) certainly does not need any introduction. The World Champion in 1972, he was a master in all areas of chess games – be it chess strategy, chess openings, chess tactics in attack and defense and chess endgames.

Sam Reshevsky (1911-1992) is a well-known Grandmaster who started as a child prodigy in Poland where he was born. He later moved to USA and won US Chess Championship no less than eight times. He was a superb positional player but also capable of brilliant chess tactics.

I presume you have already gone through the “Importance of Chess Strategy” and know about Rashid Nezhmetdinov and his playing style.

Oleg Chernikov (1936- ) was a Soviet National Master when this game was played, but went on to become a Grandmaster in year 2000.

The opening in these games follows the Accelerated Fianchetto variation of Sicilian Defense with Black’s 8. … Ng4 introduced by Reshevsky during the fourth game of his match with Fischer in 1961 (the present diagram was taken from the 6th game of that series).

Al Horowitz remarked in his book on Chess Openings: “This move (8. … Ng4) gained popularity as after this move, White can hardly avoid the exchange of minor pieces which eases Black’s game considerably”. The result of the first game vindicates Reshevsky, but you be the judge how easy it made for Chernikov in the second game!

In the second game, both players followed the same theoretical lines and subsequent variations in the footsteps of players in the first game. It is possible that Nezhmetdinov did not like the way the first game ended after Fischer’s response to Black’s 11th move and decided to chart his own path thereafter in the only way he knew, the way of a sacrifice!

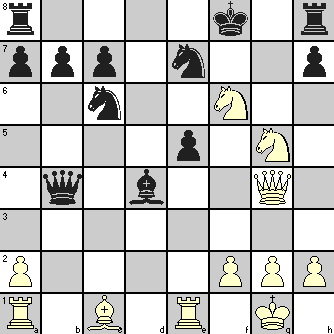

Position after 11. … Bf6:

Can you guess what Nezhmetdinov saw in this position that Fischer did not? Was it a sudden intuition/imagination or a speculation or a pre-calculated move?

This is how the games proceeded.

| 12. | Qg4 | d6 | 12. | Qxf6 | Ne2+ | White starts on his new path with a Queen sacrifice! | |||

| 13. | Qd1 | Nc6 | 13. | Nxe2 | exf6 | ||||

| 14. | Qd3 | b6 | 14. | Nc3 | Re8 | ||||

| 15. | Qd2 | Ba6 | 15. | Nd5 | Re6 | ||||

| 16. | Rfd1 | Bxc3 | 16. | Bd4 | Kg7 | ||||

| 17. | bxc3 | Ne5 | 17. | Rad1 | d6 | ||||

| 18. | Bd4 | Nc6 | 18. | Rd3 | Bd7 | ||||

| 19. | Qh6 | Nxd4 | 19. | Rf3 | Bb5 | ||||

| 20. | cxd4 | Rac8 | 20. | Bc3 | Qd8 |

In game 2, Black has the materials, White has all the space and moves. What follows will make you understand Averbakh’s warning about Nezhmetdinov in “Importance of Chess Strategy”.

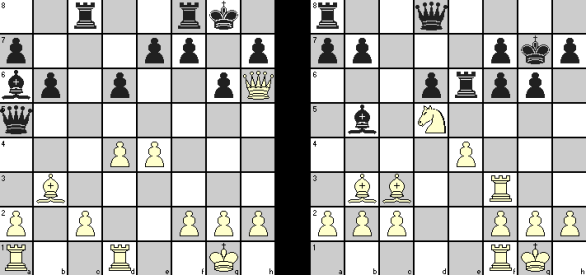

Positions after 20 moves just for comparison of the two games and to show that Nezhmetdinov was not yet done with sacrifices!

| 21. | Re1 | e5 | 21. | Nxf6 | Be2 | For 21. … Bxf1 22. Ng4+ Kg8 23. Bxe6 Qg5 24. Bxf7+ Kf8 25. Bxg6+ Ke7 26. Bf6+ Qxf6 27. Nxf6 hxg6 28. Kxf1, White wins back everything and then some |

|||

| 22. | dxe5 | Qxe5 | 22. | Nxh7+ | Kg8 | 22. … Kxh7 23. Rxf7+ Kh6 24. Bxe6 Bxf1 25. Bd2+ g5 26. Bf5 Qh8 27. h4 wins for White | |||

| 23. | Rad1 | Bc4 | 23. | Rh3 | Re5 | ||||

| 24. | Qd2 | Bxb3 | 24. | f4 | Bxf1 | ||||

| 25. | cxb3 | Rc6 | Drawn | 25. | Kxf1 | Rc8 | |||

| 26. | Bd4 | b5 | |||||||

| 27. | Ng5 | Rc7 | |||||||

| 28. | Bxf7+ | Rxf7 | |||||||

| 29. | Rh8+ | Kxh8 | |||||||

| 30. | Nxf7+ | Kh7 | |||||||

| 31. | Nxd8 | Rxe4 | |||||||

| 32. | Nc6 | Rxf4+ | |||||||

| 33. | Ke2 | Resigns |