In Chess Tactics: Catching Opponent on Wrong Foot, you were introduced to zwischenzug and were shown how the failure on the part of a reigning World Champion to consider this tactics by his opponent resulted in his defeat.

Another example of the application of this tactics will make it very clear to you. Note how a future World Champion interposes an unexpected move (zwischenzug) to surprise his opponent and bring a quick finish to the game.

The game was played between Bobby Fischer and Pal Benko in 1963 at New York during US Chess Championship tournament.

Bobby Fischer does not need any introduction and the formality was done in the article on Chess Strategy and Chess Tactics: Balancing Act?

Pal Benko (b.1928), a Hungarian born in France, became champion of his native country in 1948 and an IM in 1950. In 1957, he moved to USA and won the GM title in 1958. He was eight times winner of US Open Chess Championship.

For the uninitiated, though both US Open Chess Championship and US Chess Championship are conducted by USCF, the former is an open tournament (participants have numbered more than 500 in recent past) with entry fee, and gives out cash rewards to winners and place-holders, whereas the latter is an invitational tournament to determine the National Champion.

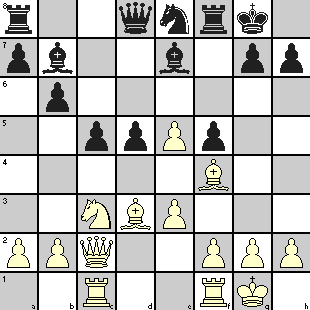

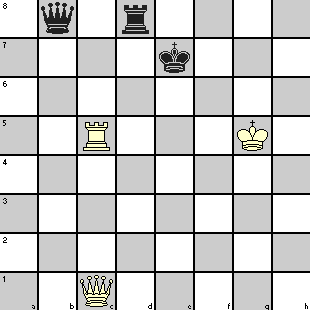

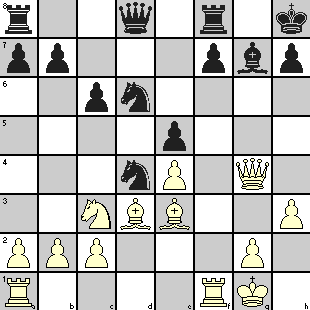

The diagram shows the position after 16 moves have been played.

| 17. | Qh5 | Qe8 | White threatened 18. Bxd4 exd4 19. e5 with attack on h7 square. But Black missed White’s 19th move, otherwise he would have tried 17. … Ne6 or 17. … f5 | |

| 18. | Bxd4 | exd4 | ||

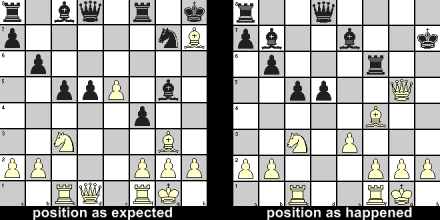

| 19. | Rf6! | The zwischenzug! Black had expected 19. e5 f5 |

||

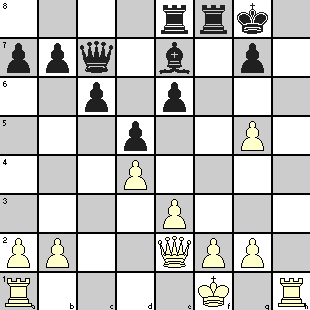

| 19. | … | Kg8 | If 19. … Bxf6 (or dxc3), then 20. e5 forces mate | |

| 20. | e5 | h6 | ||

| 21. | Ne2 | Resigns | If 21. Rxd6 then 21. … Qxe5 gives a fighting chance. But after the actual move, Black cannot avoid losing the Knight. For example 21. … Nb5 22. Qf5 wins 21. … Bxf6 22. Qxh6 forces mate |

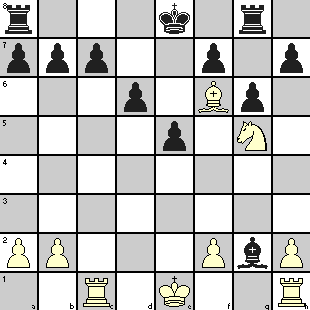

Finally, a simple but a powerful example to drive home the importance of zwischenzug as a chess tactics.

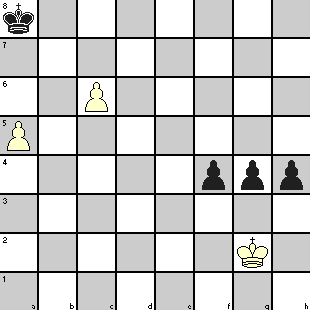

From your understanding of the article series on the chess tactics of Bishop sacrifice at h7, you can guess that the position has been derived from such type of play by White. The question is on how to continue the attack on the Black King after the castle has been broken.

Black expected that White would now try to line up the Queen and Rook along the h-file to carry out his mating threats. So, in response to 1. Qh5, he planned for 1. … Bxg5 which would give the King an escape route, whether or not the Bishop was captured by the Queen.

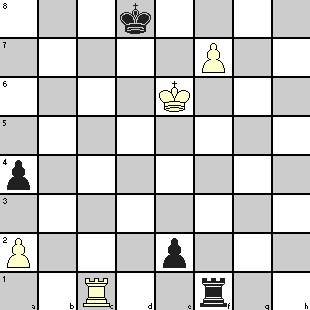

But White’s zwischenzug was to play 1. Rh8+ which resulted in:

| 1. | … | Kxh8 | If 1. … Kf7 then 2. Qh5+ g6 3. Qh7# | |

| 2. | Qh5+ | Kg8 | ||

| 3 | g6 | and mate follows |

This kind of change in the order of moves is easy to overlook and you should be alert to such possibilities both in attacking and defending.