In Chess Combinations: the eternal beauties of chess, we tried to examine our fascination for beautiful combinations. We also made the point that you do not always have to look at the games by the likes of Morphy, Marshall, Capablanca, Alekhine, Tal, Kasparov and others of their ilk for unearthing such beauties. Even amateurs at local clubs or tournaments are known to have produced brilliancies. In fact, in this series of articles we only want to look at such combinations from games of players whose names may not be universally familiar.

Besides the enjoyment you may derive from such combinations, these may also help you to understand the tactical ideas that gave rise to those surprising moves. Once you get to analyze the situations that produced it, you may be able to create some beauties of your own, who knows?

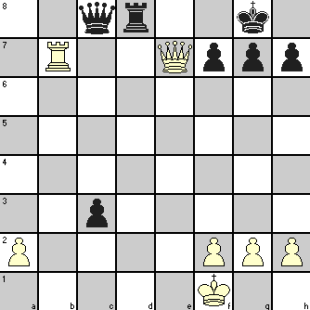

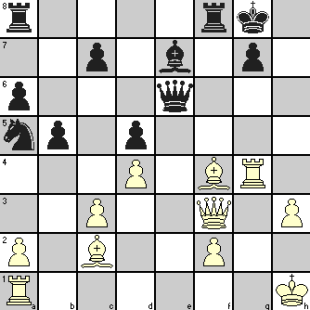

In the position shown below, you do not see any immediate danger for Black King even though White Queen is in readiness to pounce on h7 pawn if his Knight could come to g5. Most of White’s attacking pieces are on the Kingside, and either of White Rooks could come to g-file or h-file via third rank when the opportunity arises. Against this offensive battery, Black’s close defensive pieces are the Knight at e7 and Rook at f8, other pieces being mostly on the Queenside. If Black had a knight on f6 square, it would greatly help the defenses but his Knight at d4 cannot go there now as an exchange attack by White Knight at e4 will break up the castle. Let us see what transpires now.

| Position after 18. Qh3: |

|||||

|

|||||

| 18. | … | Nf4 | An attempt to drive the Queen away and to reposition Knights. |

||

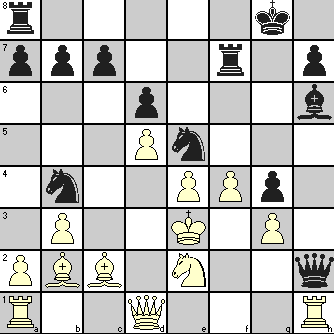

| 19. | Qg4 | Ned5 | White threatened the Knight while shifting focus on g7 pawn and creating a pin on that pawn. Black brings support for his attacked Knight and is ready to advance his KBP to chase away the White Knights. Here is a point on chess strategies. It is not considered a good practice to make the knights support each other except during the process of positioning or where situation precludes other options. Knights play much better when they are side by side (like what can be seen for White Knights) with support from other pieces. |

||

| 20. | Ra3 | Ne6 | White’s intention to bring a Rook to g-file or h-file is clear now. Apprehending a lineup of White Queen and Rook along g-file, Black makes his Knight ready to guard the g-pawn and g5 square against White’s N4. But he missed (or felt that he could tackle) the other threats by the Knight, exploiting the pin on g7 pawn. Black also missed some other defensive resources. |

||

| 21. | Bxd5 | cxd5 | We talked about the value of defensive posting of Knight on f6 square. White takes care to eliminate that scope and the exchange enabled White Knight at e4 to move without any loss of tempo. |

||

| 22. | Nf6+! | Kh8 | Once the King moved, the g7 pawn got unpinned and was ready to capture the Knight which was a threat to Black’s h7 pawn if White’s Rook came to h-file. |

||

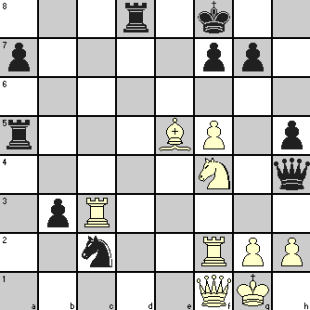

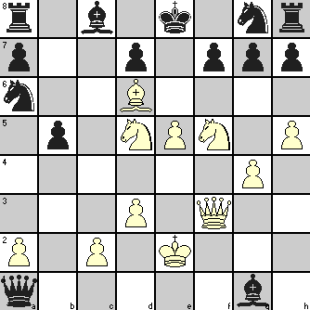

| Position after 22. … Kh8 |

|||||

|

|||||

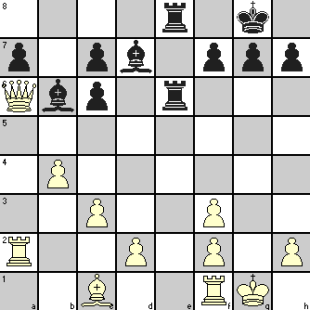

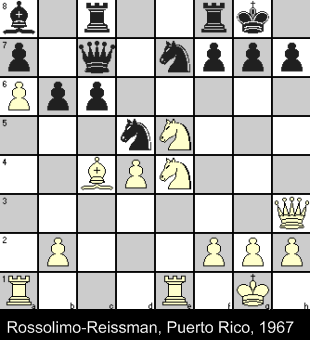

| 23. | Qg6! | The bolt from the blue! White threatened 24. Qxh7#. Let us see the possibilities: 23. … fxg6 24. Nxg6+ hxg6 25. Rh3# 23. … hxg6 24. Rh3# 23. … gxf6 24.Qxf6+ Kf8 25. Rg3+ Ng5 26. Rxg5# 23. … gxf6 24.Qxf6+ Ng7 25. Rg3 Rg8 26. Nxf7+ Qxf7 27. Qxf7 wins 23. … Ng5 24. Qxg5 g6 25. Qh6 with mate to follow. |

|||

| 23. | … | Qc2 | The only option left out! |

||

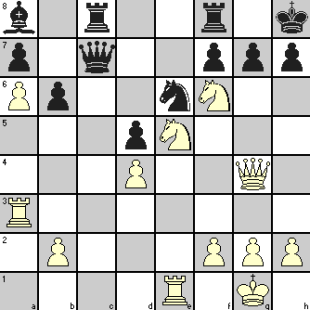

| 24. | Rh3 | Resigns | 24. … Qxg6 25. Nxg6+ fxg6 26. Rxh7# or 24. … h6 25. Rxh6+ gxh6 26. Qxh6+ Qh7 27. Qxh7# or 24. … Ng5 25. Qxg5 gxf6 26. Qxf6+ Kg8 27. Rg3+ Qg6 28. Nxg6 fxg6 29. Rxg6+ hxg6 30. Qxg6+ Kh8 31. Qh6+ (to guard against … Rc1#) Kg8 32. Re7 Rf7 33. Qg6+ Kh8 34. Qh5+ with mate in two moves. |

||

A very effective demonstration of the power of pin and the mobilization/coordination of pieces.