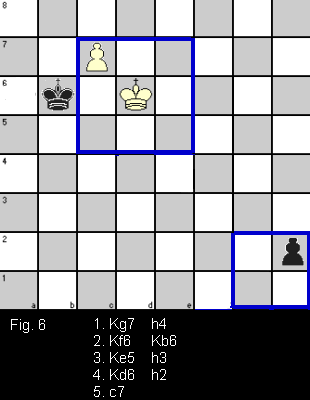

In Working out Chess Combinations, you could work out an eight-move combination by identifying the strengths and weaknesses of both sides and to some extent worked your way backwards to find the moves that created the winning combination. But in the previous examples, there were quite a few pieces on board and the mobility, at least for some pieces, was restricted so that you could eliminate a good number of possibilities.

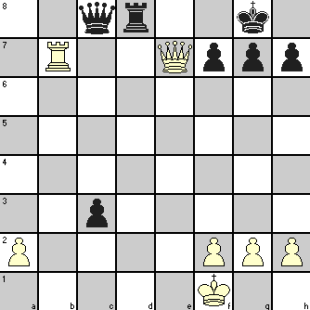

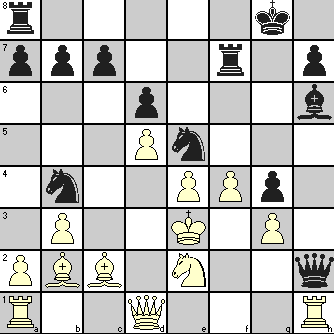

In the problem that we are posing now, there are only a few pawns and some heavy pieces on the board which is open to both sides for moving respective Queen and Rook. In fact, many beginners get daunted by such positions because they think that there are too many moves possible for their Queen and Rook and taken together with the responses from opponent’s Queen and Rook, the number of combinations may be overwhelming! Let us now examine if we risk getting bogged up in the maze of moves!

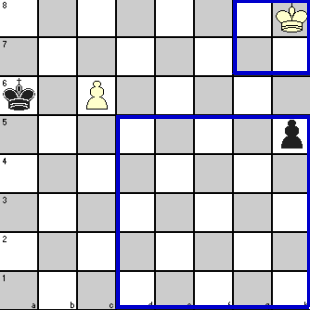

I do not have to say who has got the move because if it were White, this discussion would not be necessary. With Queen and Rook on the seventh rank, it is only a matter of two checks by the Queen to checkmate the Black King. But Black having the move, you have to be acutely aware that Black cannot let go of checks if aforesaid action by White has to be stalled. You should also note that in absence of Black Queen and Rook from their base rank, Rb8+ by White is enough to checkmate Black King.

If you consider Qc4+, you know that White Queen cannot interpose by Qe2 as in that case Rd1+ mates the White King (the Queen being pinned cannot capture the Rook). So only option for White is to move the King and e1 is the only escape square available for that. But then Black’s only move is Rd1+ and after Kxd1, he can try Qd3+. Of course White cannot play Kc1 (you work that out), but Ke1 allows still one more check by Qd2+. The White King has to move to f1 but further check by Black at d1 or d3 allows White to interpose with his Queen (by Qe1 or Qe2). After this, Black soon runs out of checks and that puts paid to further resistance by Black. So this line is not tenable.

That leaves Black with only Rd1+ when White’s only option is Ke2. If Black now tries Rd2+, White King can retreat to previous position and Black has nothing left but a draw by repetition of moves. But will you be that desperate for a draw before exploring other options?

You can see that Qg4+ supports the Rook and allows White only two options:

(i) move King to e3 (i.e., Ke3)

(ii) interpose with pawn by f3

It may look that Ke3 is not viable as Black can play Re1+ to capture White Queen. But can Black do that? As soon as Black plays a non-forcing move like Rxe7, White’s Rb8+ leads to checkmate of Black King!

On Ke3 by White, Qd4+ forces the King to move to f3, as Ke2 allows Qd3# mate by Black. With King at f3, Black’s Rd3+ forces King to e2 (you should think why interposition by White Queen at e3 is now futile) but next check by Rd2+ brings King back to f3. Now Black’s Qxf2+ drives the King into the wide open and it should be possible for you to keep checks going with Queen and Rook for a checkmate if King remains on e-file, but if it moves towards g-file, a pawn check at appropriate time ends the White King’s journey!

What about the other option of interposing by pawn move f3? Trying to guard the diagonal, White exposes the King along rank 2 and Black can play Qxg2+! White cannot take the Rook as that would allow checkmate by Qd2#. So the only move for White is Ke3. On Qd2+, the King is forced into the open by its only move Ke4. Black keeps pressure on by Qd4+ and King is driven into the hands of the Black pawns and Black Rook can also attack by Rg1+ when King moves to g-file. You can certainly work out the rest.

So you are now sure that after Black’s first move of Rd1+ in the diagram position, White King cannot avoid checkmate whatever it may do.

In the actual game, played between Heinrich Wolf and Jacques Mieses at Monte Carlo in 1902, White chose the option (ii) at his 30th move and Black delivered checkmate after another 5 moves.

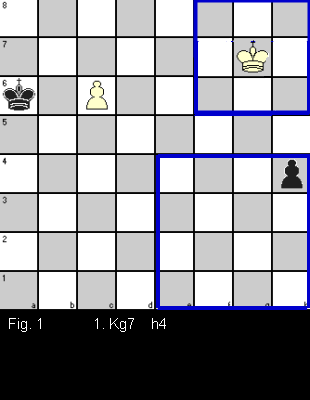

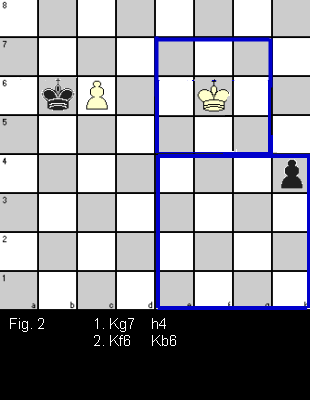

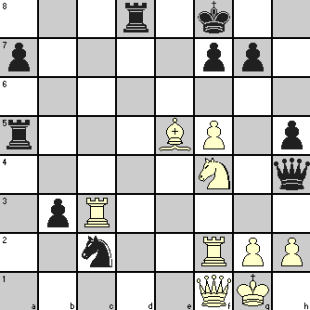

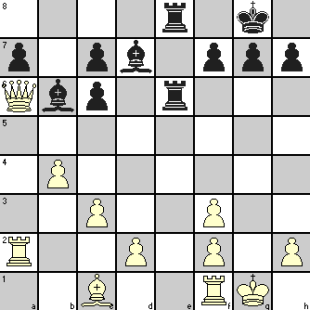

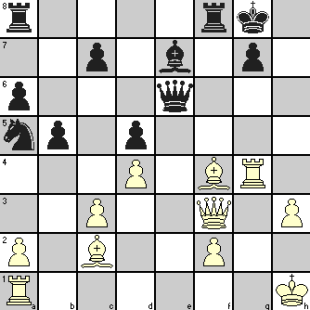

So far as this and the examples in related previous articles on chess combination are concerned, we could find the way by following a methodical approach. But I also told you that such system may not work universally. Situations where a combination came out of the sheer brilliance of a mind and could not be seen even by a Grandmaster opponent, such analysis may not show the way beyond a certain step. This is particularly true where a move makes sense only when seen in context of subsequent moves and the brilliancy is realized by taking all these moves together. The following example is a case in point.

The position shows that Black has one Bishop less but he has two passed pawns extra, one being only two moves away from promotion. Black Rook at a5 is in a position to capture the Bishop at e5 and also to move to a1 for capturing the Queen. Obviously, it is White’s move now and he has to tackle these threats, possible only by forcing moves on Black King to retain a tempo. On the plus side, White has Rook and Queen lined up on f-file and if the line can be opened, he can plan his assault on Black King, possibly with help from his Bishop attacking the g7 pawn and the Rook at c3 moving up to 7th or 8th rank when it can do so. But while working out the attacking plans, White cannot afford to lose a tempo, otherwise Black will launch his counter-attack as described above.

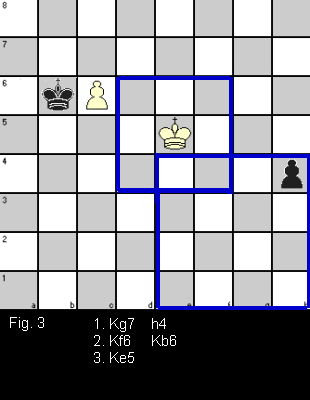

It is easy to see that White can play Ng6+ creating a fork on the Queen and White will be obliged to capture the Knight with f-pawn. White in turn can play fxg3 thereby opening the f-file and the discovered check retains tempo with White. It is apparent that Black cannot play Ke8 (because of White’s Rf8+ and Qf7#) or Ke7 (due to White’s Rf7+ / Qf5+ / Bg3+ / Qd3#). So the only possible move by Black that does not lose immediately is Kg1.

If White plays Rf7 with intention to play Rxg7 leading to mate, Black can counter this by capturing the Bishop with Rxe5 and threatening Re1 next, when White’s plans fall through. Were White’s Rook not standing in his Queen’s way, Qf7+ would be possible but as it stands now, White cannot afford to lose tempo by playing Rf7.

This far could be analyzed through a systematic approach, but can White take his initiative forward beyond this point? It is very difficult to imagine and needed real brilliance by White to make this a famous combination because of his next two moves!

You may give it a try before going through the following moves.

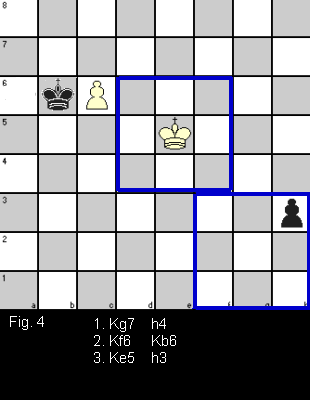

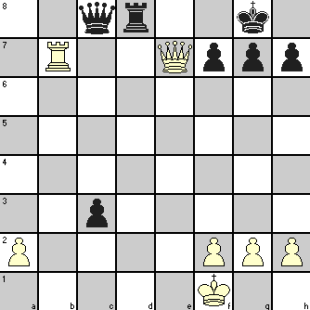

From the diagram position, the game proceeded as follows:

| 1. |

Ng6+ |

fxg6 |

|

|

| 2. |

fxg6+ |

Kg8 |

|

|

| 3. |

Rc8! |

Rxc8 |

|

The move by White together with his next move were difficult to anticipate

|

| 4. |

Rxc2! |

Rf8 |

|

White’s move cleared f-file for Queen while retaining the tempo.

White’s Rook cannot be captured because of the threat Qf7+ leading to mate.

|

| 5. |

Rc8 |

Qe7 |

|

White keeps attacking the f7 and f8 squares and Black tried to counter these threats

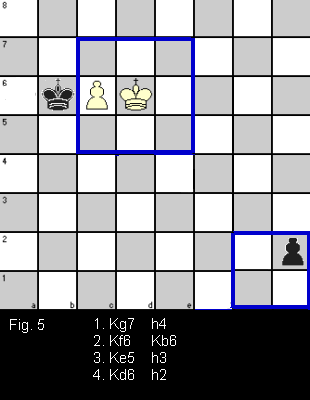

|

| 6. |

Qc4+ |

Kh8 |

|

6. Bd6 can be countered by 6. … Ra1+

|

| 7. |

Qh4 |

Ra1+ |

|

Black has nothing better to do as 7. … Qxh4 allows Rxf8#

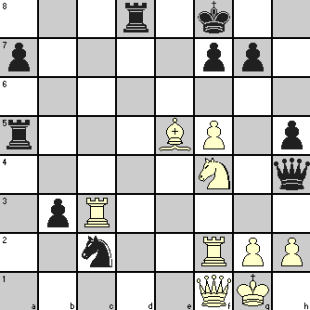

|

| 8. |

Bxa1 |

Qe3+ |

|

desperation!

|

| 9. |

Kh1 |

Rxc8 |

|

While starting on his combination, White must have seen that Black has no more check after his King moved to h1. |

| 10. |

Qxh5+ |

Kg8 |

|

|

| 11. |

Qh7+ |

Kf8 |

|

|

| 12. |

Qxg7+ |

Ke8 |

|

|

| 13. |

Qf7+ |

Kd8 |

|

|

| 14. |

Bf6+ |

1-0 |

|

Checkmate is inevitable on White’s next move |