From the mails received from many beginners, it appears that they are often at a loss in finding the best sequence of moves they should follow in response to a move by the opponent. In effect, they are asking how to make the calculations for a combination (a sequence of moves to achieve a specific purpose like mating the king, winning some material, gaining space etc.).

In the opening phase, they need to understand the strategic ideas and tactical possibilities for the opening or defense they adopt. With regular practice, these can become fairly automatic response, so we presume that the problem is not for this phase of the game.

But after entering the middle game where each has to chart his own path, the aforesaid problem can surely be significant. So how does one proceed?

You must be very clear about the ideas you have been following till you reached such a stage. Whatever move supports or enhances those ideas are good, whatever takes away or counters those ideas are bad – unless the board situation makes it necessary to abandon the earlier plans and formulate new ones.

One thing is certain – you know what you have in your mind! Problem is to guess what your opponent is thinking. But you get clues from the moves that he is making and do not reject any move by opponent as silly or a mistake unless you become sure of it by observing the disposition of his pieces.

This brings us to the essence of analysis – the moves that have been played (you can see those) and moves that are going to be played (you guess those) because those will have some link to the moves played not only by the opponent but by you also. So think about the purposes behind any move and whether those are offensive, defensive or a mixture of both.

Defensive moves should be relatively easy to identify as those will try to counter threats you have posed by your moves or threats that your opponent reasonably expects you to create. When planning your attack, you may have expected these responses and decided on your counter-action. But if the response is unexpected, try to see if there is a hidden agenda of a counter-attack or creation of a new defensive resource (like a stalemate possibility) and prepare your next moves accordingly.

Offensive moves like a direct attack can be seen easily but those hidden behind some combination may often appear innocent. So, all moves other than obviously defensive ones should be analyzed for their inherent ideas.

Why did your opponent make a particular move? It may be for:

- attacking your piece or pawn (if that is undefended, you can take defensive action but be suspicious if opponent aims at a defended piece, particularly using a piece of higher value as this may be a precursor to a sacrifice or more forces may be on the way)

- getting a piece to a better position (may be strategic but be sure that it does not pose any immediate offensive possibility)

- opening the line for another piece (examine if that creates attacking chances)

- vacating a square for another piece or pawn (see which piece or pawn can occupy that vacated square and what they can achieve)

- control of some other square (look for the piece or pawn which can occupy that square and their possible aims)

- providing support to a piece or pawn that is not under your attack (find why he expects some action around that piece)

- creating a decoy to lure some critical defender away (note which of your defender is targeted and then see which of your pieces or squares will suffer if that defender moves – gives you idea of where the attack may come)

- driving your pieces away when capture is not possible (see how it can help your opponent if your piece is shifted)

- starting a long-range pin or skewer (be aware of this whenever you see any opponent piece taking up a line to your King, or a piece of lower value is positioned in the same row, file or diagonal to your piece of higher value. Even though there may be other pieces or pawns interposing at that point of time, examine the possibility of those getting removed in some way to activate the pin.)

- initiating the process towards discovered or double checks (these are always dangerous and forcing in nature, the presence of a piece capable of delivering check and in line with your King should alert you about such chances)

- offering a sacrifice (be careful of the possible consequences of accepting the offer unless it is forcing, particularly in the light of possibilities listed above)

Though we have written above assuming you to be the defender, you may keep the same points in mind to plan your own attacking methods and to decide which of these will be most appropriate in a particular situation.

If you have identified some weakness in your opponent’s position and the possibility of gaining an expected advantage, you may even calculate backwards. Visualize the situation you want to achieve with your and opponent’s pieces in required positions. Then work backward on how the pieces concerned can reach those specific positions from their current locations and you have got your desired combination!

It may look simplistic and I do not claim that it is always possible, but if you can discipline yourself to think in those lines and practice such actions, these thought processes will become your second nature over a time.

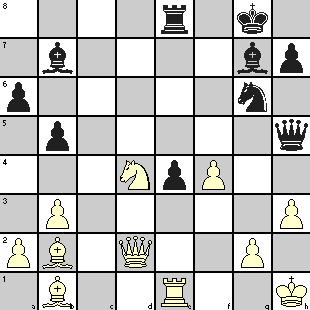

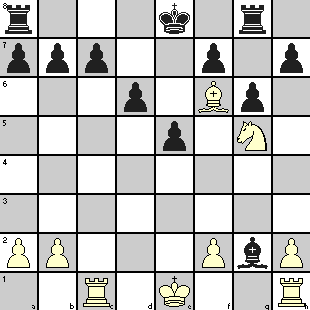

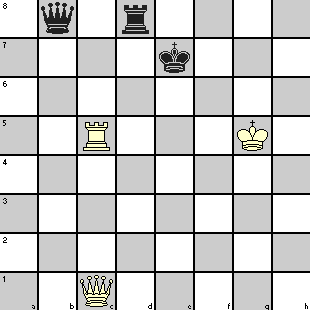

A simple but concrete example may make the process clearer to you. Take a look at the following position with White to move.

You can see that Black has a material advantage of two rooks and a bishop (of course engineered by White to get his attack going)! Black Queen and Bishop, though sitting in White’s base rank, cannot deliver any viable check and has practically been sidelined. Black’s QN is uselessly posted at the wrong edge of the board and his other pieces are still at their home positions! Black’s King is exposed in the center while White’s Knights and Bishop are dangerously close to Black King with the White Queen ready to come up along the semi-open f-file.

Once you have assessed the position and discounted any viable threat by Black, what moves by White can you think of? A closer look at the Black King shows that of the three squares (d8, f8 and e7) accessible to the King, only d8 is viable as f8 is denied by White Bishop and e7 by both Knights and the Bishop as well. Even if the King moves to d8, it cannot go further via c7 as that square is controlled by the Knight at d5.

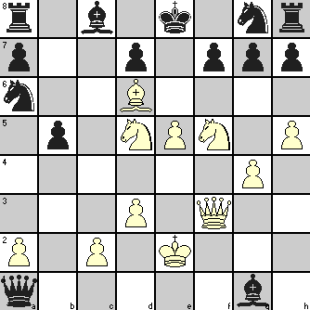

Conclusion:

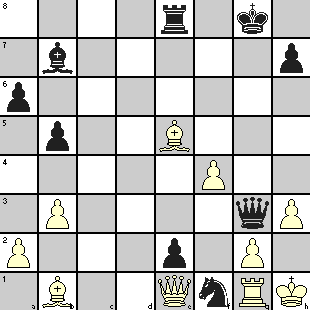

If you can deliver a check now (Nf can do that from g7 with impunity), King has to move to d8 and check by Bishop at e7 with support from the other Knight would create checkmate – provided Black’s KN could be forced to relinquish its hold on e7. You also realize that once the King moved to d8, White Queen can move up (remember that the Knight has moved to g7) to f6 for a checkmate unless Black’s KN intervenes. But this Knight cannot guard e7 if it captures at f6!

So the sequence of moves becomes clear –

1. Nxg7+ Kd8

2. Qf6+ Nxf6

3. Be7#

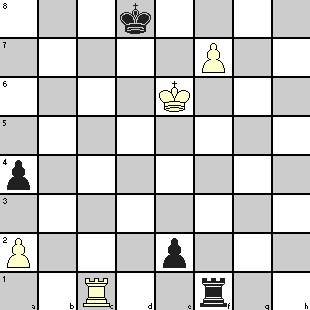

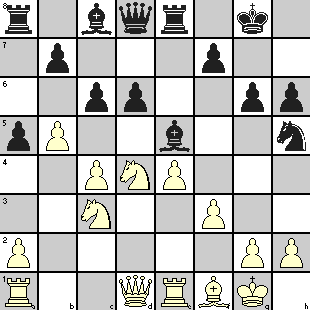

If it interests you, this game was played between Anderssen (the best player around that time) and Kieseritzky at London in 1851 and the game has earned the title of “The Immortal Game” because of the way White conducted his attack. I am sure any online chess repository will have this game and you can play through the full game – but try to analyze and predict the moves by White (the game lasted 23 moves).