One of the important set of pieces with unique advantages of moving forward and backward only on verticals and horizontals and not otherwise is the rooks. The importance of the rooks can be assessed by the fact that the value of two rooks is more than the value of the Queen. No other combination of the major and minor pieces gives a value more than the value of the queen in the game of chess. The rooks are basically stationed at the flanks at the start of the game. As part of the opening strategy, it is imperative that the players try to bring these two rooks into play by preferring to castle and prepare the rooks for further development.

At the start of a typical middle game stage, one could invariably find both the rooks occupying the back ranks while all other minor pieces leave that first rank and take interesting positions in the other ranks. Most of the time even the Queen moves out of the back rank, but the rooks will be stationed there before preparing for the development.

It is imperative that which of the two rooks should be moved as part of the development or defence should be correctly assessed, based on the evaluation of the position of the board, and a wise decision is taken. The choice of the wrong rook for movement will not only complicate the position, it might give away the advantage to the opponent to pounce on the weakness.

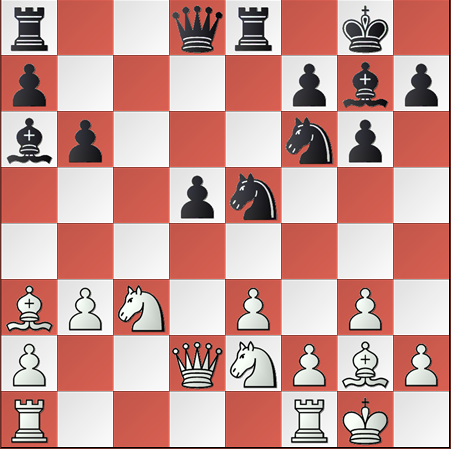

To emphasize this important fact, let us look at a part of the game played in German Bundesliga by two grandmasters, where a wrong decision by white has forced him to part with the control over the board and ultimately after great defending and futile attacking, had to settle for a draw.

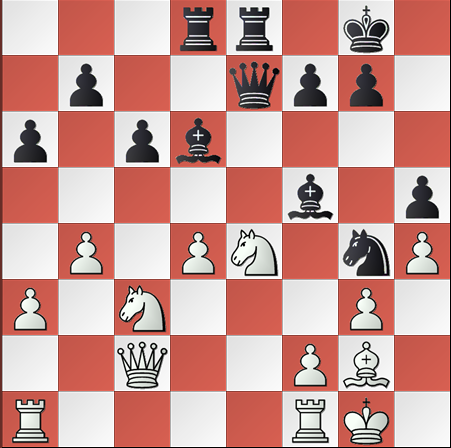

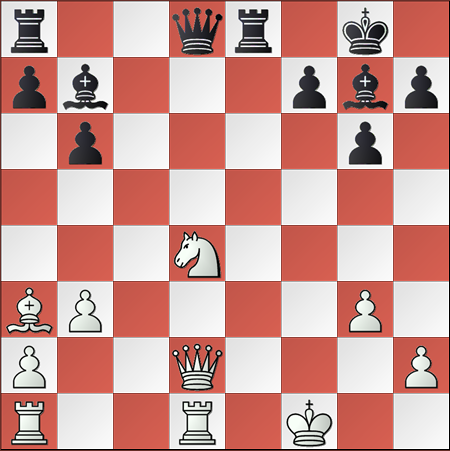

This is the position of the game after 15 moves, and it is the turn of the White to make a move.

(White to move)

A cursory look at the position indicates that both the players have developed their pieces fairly well, and are in the midst of an intriguing middle game. It is obvious that White would want to move his rook to the e1 square to share the advantage of the open e file. Here comes the dilemma as to which of the two rooks – rook at c1 or the rook at f1 – that should be moved to the e1 square – is the problem.

The merits of moving the rook at f1 to e1 include – having two rooks at each side – queenside and the kingside – and exercising control over the “c” file and the “e” file. On the contrary, moving the rook at c1 to e1 means the rook at f1 is blocked.

White decided to go ahead with the second option of moving the rook at c1 to e1.

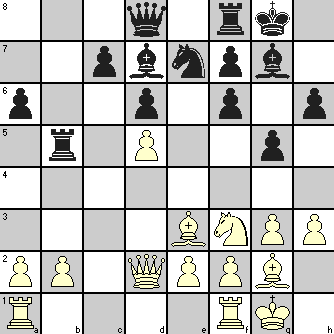

The moves are as follows:

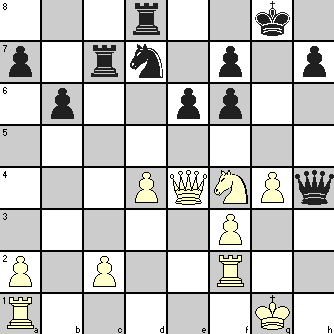

| 16. | Rce1 | Qd6 | |

| 17. | Re3 | …. | White anticipated that an exchange of Rooks as:

1. ….. Rxe3 2. fxe3 ….. would strengthen his position with the Rook at f1 |

| 17. | …. | Bg7 | Black did not accept the invitation for exchange |

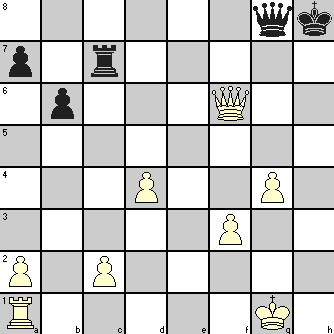

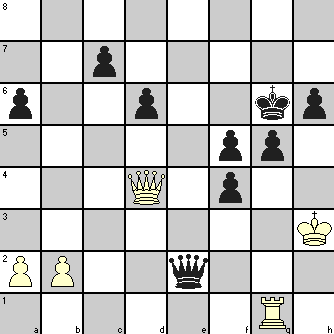

The game continued further and after another 30 moves or more, both the players agreed for a draw.

This is a nice example, which emphasizes that every move, especially the wrong ones such as this one by white, should be judged on its merits.